Documenting Plant Diversity: Jasper Ridge's Herbarium

HerbariumCrew.jpg

by Eliza K. Jewett (2005 Views Article)

Think "herbarium" and you may have an image of dim, silent corridors reeking of mothballs, where aging metal cabinets conceal folders of faded dry plants from all but the expert visitor. An herbarium may seem like a forgotten holdover from another century, out of place in today's practice of science.

Yet in fact herbaria are still highly relevant to current research in ecology and evolutionary biology. Large research herbaria provide reference material for identifying and locating plants, a means of tracing morphological or ecological changes over time, and even genetic material for creating molecular phylogenies. Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve's herbarium is a relatively small teaching and reference collection, but it still provides important information to the community at the Preserve--and as evidenced by the construction of the Oakmead Collection Rooms in the Sun Field Station, it is far from forgotten or outdated.

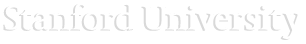

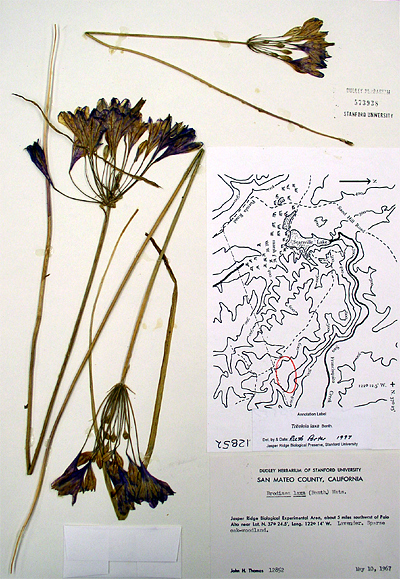

The collection now residing in the Oakmead Collection Rooms was given to Jasper Ridge by Stanford professor John Hunter Thomas a few years before his death and made possible by a generous donation from Jasper Ridge docent, Leslie Sun. In the 1960s, Stanford University dissolved its Division of Systematic Biology (in keeping with the view that cellular and molecular biology were the up-and-coming important fields in biology); this ultimately led to the transfer of the University's impressive Dudley Herbarium to the California Academy of Sciences in 1976*. When the transfer occurred, Thomas kept a small collection of local specimens to use for teaching.

Now at Jasper Ridge, these 5,000-6,000 specimens were mostly collected and/or identified by Thomas himself, but do include some sheets that date back as early as 1867.

At first the collection was kept as well as possible in the conference room of Searsville Lab. In these shared quarters, the round worktable was as likely to be used for working with live plants or eating lunch as for examining herbarium sheets. Docent Ruth Porter volunteered to help put the collection in order. As she began cataloging and sorting the specimens, she realized that about 2,000 (one third of the collection) had not been identified or completely labeled. Recognizing the immense magnitude of the task, she called for additional assistance. Toni Corelli, docent and expert on local plants, volunteered to help with the identification. Within the next several years, docents Ann Lambrecht and Carol Zabel joined the team of volunteers and Sally Casey, a grass expert, offered expertise as a volunteer consultant. Docent John Rawlings has most recently joined the team, and is helping with identification of grasses.

Their task quickly expanded from merely organizing the collection to trying to determine fundamental knowledge about the plant species of Jasper Ridge: what is present in the Preserve, and where is it? The first step toward answering these questions was to compile a plant list of all the species that had been recorded at the Preserve. The team created a database listing all the identified specimens in the collection, then added species from Herb Dengler's plant list, Thomas's notes, and other historical sources (and updated the names to those currently accepted) to create the Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve Vascular Plant List. According to the second edition of the list, "822 vascular plants have been recorded as being present now and/or in the past." The underlining is crucial: some species on the list may no longer be present in the Preserve--such as the Cannabis (marijuana) found and removed in 1982--while other species may be present but have not yet been found and listed; two new Piperia (rein orchid) species were found within the last several years. To try to address the question of which species are still present, Zabel and Lambrecht walk the trails regularly, recording the plant locations of relatively uncommon species, keeping an eye out for anything unusual, and following leads provided by researcher, program affiliate, and instructor Irene Brown.

Others are welcome to assist with this process; sector map booklets for pinpointing locations are available for loan from the Jasper Ridge library or herbarium.

The volunteers are also working to positively identify all the unlabeled specimens in the collection. They use their own expertise, botanical keys, comparison specimens from the Carl J. Sharsmith Herbarium at San Jose State (of which Corelli is curator), and, for particularly problematic groups, consultation with outside experts such as Sally Casey, who checked the identification of nearly all the grass specimens. They are also re-checking the previously named specimens against the most current scientific names in The Jepson Manual (1993), and indicating any updates with annotation labels.

After nine years, they say the job is nearly complete. Several other projects are also ongoing. Lambrecht has entered all the information from the label of each herbarium sheet into a computer database, and is now maintaining the database with name changes and updated information. Porter's husband, Dave, has scanned the 1,500 plant slides in the Jasper Ridge library; additional requested photos have been taken by Chris Andrews. The plant database and scanned photos are available online in the Affiliates section of the JRBP web site (password required).

The construction of the Sun Field Station has added an exciting new chapter to the herbarium's history. Creating a convenient, archival space for Jasper Ridge's plant specimens was a priority in the design of the building, and was largely made possible by a naming grant from the Oakmead Foundation. Porter was intimately involved in planning for the herbarium, from determining the space allotted in the building plan to recommending the location of the electrical outlets. Housed in the west end of the building, the room is bright, clean, and spacious--and solely dedicated to preserving and maintaining the collection. The green construction ethic that pervades the entire building is evident: Former executive director Philippe Cohen salvaged John Hunter Thomas's metal herbarium cabinets from Stanford storage; archaeologist Laura Jones found a long table on campus (a lab top was added later); Ann Lambrecht helped Jasper Ridge obtain nearly new lab cabinets from her former employer, for use in the herbarium and throughout the building. (An exception: the room is air-conditioned to ensure a cool temperature optimal for the plants; it is the only room in the building with air-conditioning.) Long-arm microscopes for examining specimens top the counter. A large freezer decontaminates specimens on a rotating basis. A sign-in book shows that the herbarium sees frequent use from students, faculty, docents, and other visitors. The volunteers have clearly put their expertise to work to make the new space a true herbarium. Indeed, "the herbarium is much smaller, but much better organized than other herbaria," says Will Cornwell, a graduate student in the Ackerly lab.

laxa1.jpg

Cornwell's work is an excellent example of how the herbarium is used in current research. When starting his research on the community assembly of woody plant species, he needed to learn to distinguish relevant plants, often within tricky genera like Ribes and Salix. He was able to unequivocally identify samples from the field by comparing them with specimens in the herbarium. "You can do it off the Jepson manual," says David Ackerly, acting associate professor of integrative biology at UC Berkeley, "but I think plant systematics still makes more accurate reference to collections, to really make sure you have what you think you have. That's why we call it a reference herbarium." It is particularly helpful that the specimens are local, since they show the specific variation that exists within the Preserve. Katherine Preston and Jessica Ruvinsky, former members of the Ackerly lab, have used the herbarium to identify plants as well as to glean species location and habitat information useful for finding potential study sites. Preston and Cornwell brought students from Peter Ray's plant taxonomy class to visit the collection to show what an herbarium is, how it is used for research, and how specimens are prepared. According to Philippe Cohen, "the value [of the herbarium] will grow and accumulate over time, similar to a rare book collection at a library." Older specimens will become particularly valuable.

This archival importance of the collection means that active maintenance will be permanently required. In the past year, five cabinets, a long arm microscope, and improved lamps have been added. Though the new room is much better than the previous space, it is not isolated. A sticky mat outside the door helps cut down on the dirt and contaminants brought in on shoes, but the team is "constantly on the defensive against bugs." An invasion of ants, for example, could potentially bring in other organisms that could do damage to the collection. The herbarium volunteers actually clean the rooms themselves using a separate vacuum (to avoid cross-contamination) and special products; most regular cleaning products would destroy the archival state of the collection. For now, the principal aim of those working in the herbarium is to lay its foundation as an organized, effective reference tool. In the future the goals may expand. The herbarium does not distinguish between native and non-native plants--in theory, it ideally should contain a specimen of every plant that has ever been found on Jasper Ridge soil. As new species are found, new exotic plants invade, or better specimens are needed, Jasper Ridge must decide which plants (if any) it is appropriate to collect for the herbarium. Now that the existing specimens are nearly all named and databased, the volunteers are beginning to fill in gaps in the collection, mostly in the grass family. They are collecting only a single specimen of each missing species, unless the species is rare or has only a limited population within the Preserve. For example, the recent finding of two individuals of the threatened orchid Piperia michaelii is an exciting new addition to the plant list, but no one would consider physically collecting the plant--instead, photographs of different life stages, showing diagnostic characters, have been taken.

centaurea2.jpg

The herbarium could be helpful in determining how species composition and species themselves change over time. By showing what once grew on the Preserve but is no longer found there, the herbarium can help determine what species are being lost. Or it could possibly take a role in mapping the distributions of plants throughout the Preserve. Since there is such an important relationship between plants and invertebrates, and so much research done at the Preserve that ties into herbivory and invasive species, Philippe Cohen would like to see Jasper Ridge's collections someday expand to include invertebrates. He would also like to see the specimens cross-referenced with those in other herbaria, such as the Dudley and the Sharsmith, as a component of the data available online.

While everyone may have a different perspective on the future plans for the JRBP Herbarium, one thing is certain: the work that the herbarium volunteers have done--and continue to do--is greatly appreciated. As Katherine Preston put it: "The herbarium volunteers have provided a tremendous service to the Jasper Ridge community by putting together and maintaining the herbarium. It's easy for all of us to underestimate the work they continue to do there, but it's an extremely valuable resource."

What is an Herbarium?

An herbarium is analogous to a library, but rather than books, it archives actual plant specimens. Each plant is flattened, dried, and attached to an individual sheet. Herbarium specimens provide an invaluable physical record of each plant, far more complete and scientifically useful than any written description or drawing could be.

Creating and Maintaining Herbarium Specimens

- If possible, an entire plant, including roots, is collected in the field. (Current botanical collecting expeditions also take digital photographs and collect additional material for DNA analysis.)

- specimen is arranged to show all parts to maximum advantage, then flattened using a plant press (cardboard and wooden frames that are tightened around the specimens using straps).

- The specimen is dried in the air or in an oven.

- The specimen is sterilized by freezing at -18° C for at least one week.

- Using special archival materials, the dry specimen is mounted to heavy paper.

- The specimen is identified using floras, comparison to other specimens, and/or the opinions of experts.

- The species name, collection location and date, habitat description, map or global positioning system coordinates, collector's name, and any other pertinent information are typed on a label, which is attached to the sheet.

- Specimens are organized by family, then genus and stored in metal cabinets, with care taken to prevent insect or other damage. Properly archived specimens can last indefinitely.

- Specimens are re-frozen once a year on a rotation to ensure preservation.

- Green plants are not allowed into the herbarium room. They are sealed in a Ziploc bag; other herbaria may use microwaves.

Eliza K. Jewett is a Jasper Ridge docent and freelance science illustrator, graphic designer, and writer. Visit her web site at www.elizajewett.com.