Barcoding life: Little Steps, Big Questions

We’re Jen and Hilary Bayer, 20-year-old twins from Palo Alto. For as long as we can remember, we’ve been exploring nature. Several times during childhood we visited Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve with Stanford student friends of our family who were docents. Since then we’ve aspired to learn more about, and contribute to work being done at the preserve.

Throughout our lives we’ve become increasingly aware of disappearing biodiversity. In our own backyard birds once common are now rare, or were last seen years ago. In the Sierra, where our family vacations each autumn, trees are dying wholesale as a result of record heat, drought, wildfire, and pest infestations. As we’ve come to better understand the consequences of these losses we’ve become more determined to slow or stop them, and to contribute to protecting biodiversity around the globe.

About nine years ago, Dan Janzen and Winnie Hallwachs, University of Pennsylvania faculty and pioneering conservation biologists who’ve led in protecting and cataloging biodiversity in large swaths of diverse ecosystems in Costa Rica, stayed in our home while fund-raising in the Bay Area. Inspired by their work and encouraged and guided by family friend, JRBP docent, and San Diego Barcode of Life founder Brad Zlotnick, we initiated Silicon Valley Barcode of Life.

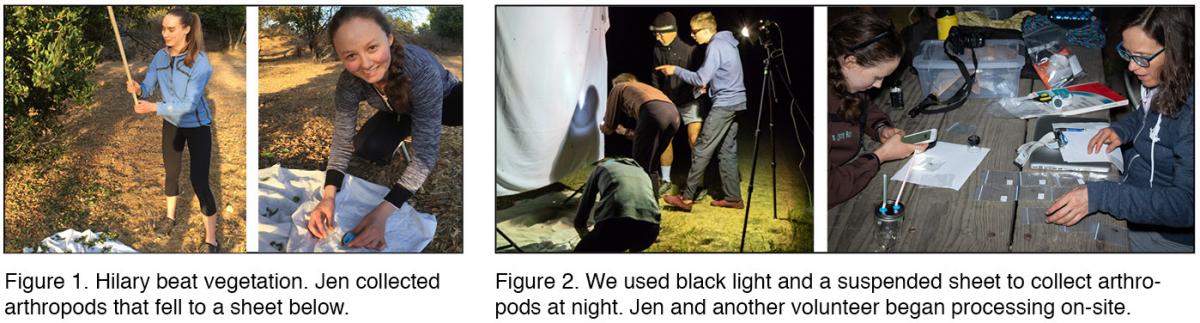

With SVBOL we aim to engage people in learning about the value of, and threats to biodiversity, and in acting to protect it. We started slowly, learning basics about collecting arthropod specimens and preparing them for DNA sequencing. When we told friends about what we were doing, some offered to help.

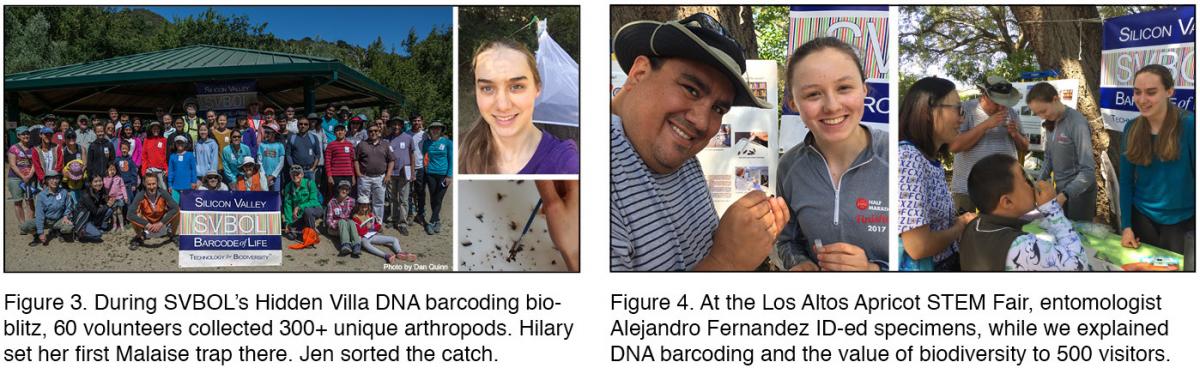

In June of 2018 we conducted SVBOL's first public fieldwork event, a DNA barcoding bioblitz at Hidden Villa. More than sixty volunteers collected 300+ unique arthropod specimens. Since then we've taken SVBOL into schools and other community settings. An Apricot STEM Fair at the Los Altos History Museum was opportunity to interact directly with 500+ curious visitors.

About a year after we began SVBOL, a friend who’d just graduated from Stanford suggested that we seek advice from Rodolfo Dirzo. He was wonderfully encouraging and invited us to attend meetings of his lab. There we’ve learned about his and his students’ work to conserve biodiversity. We’ve been especially inspired by their outreach to young people who otherwise have little opportunity for hands-on learning about nature. Jess Martin, a grad student we met in Dirzo lab meetings introduced us to Liz Hadly, who was enthusiastic about our DNA barcoding at JRBP. This was a dream come true!

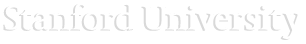

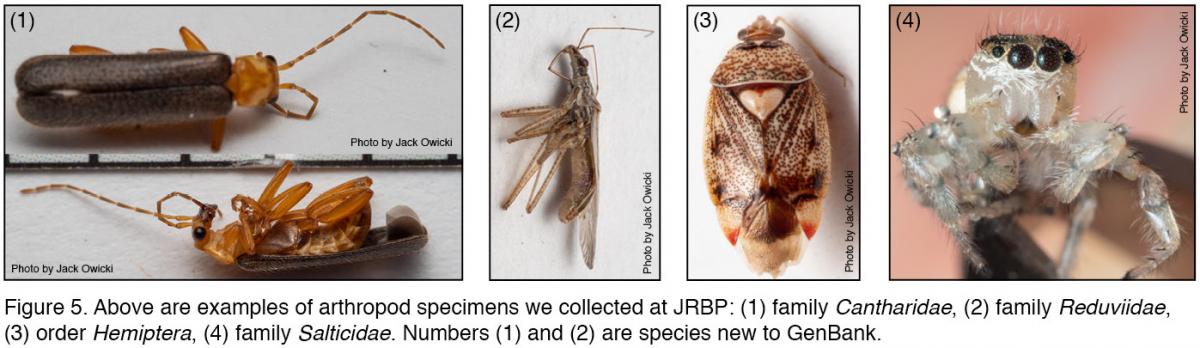

With Jack Owicki, an advisor to SVBOL and JRBP docent, we collected thirty arthropod specimens (examples in Figure 5, above) at JRBP. Every scientist relishes “Aha!” moments. At our last collection site we had one of those for which Jen paid with an “Ouch!” Hilary was beating vegetation over a sheet, while Jack ID-ed, and Jen sampled. As Jen grasped an interesting-looking specimen to place into a vial, it bit her. Jack quickly identified it as a type of assassin bug, which injects a toxin when it bites, causing pain comparable to that of a wasp or hornet sting. Wiser for the experience we decided to call it a day.

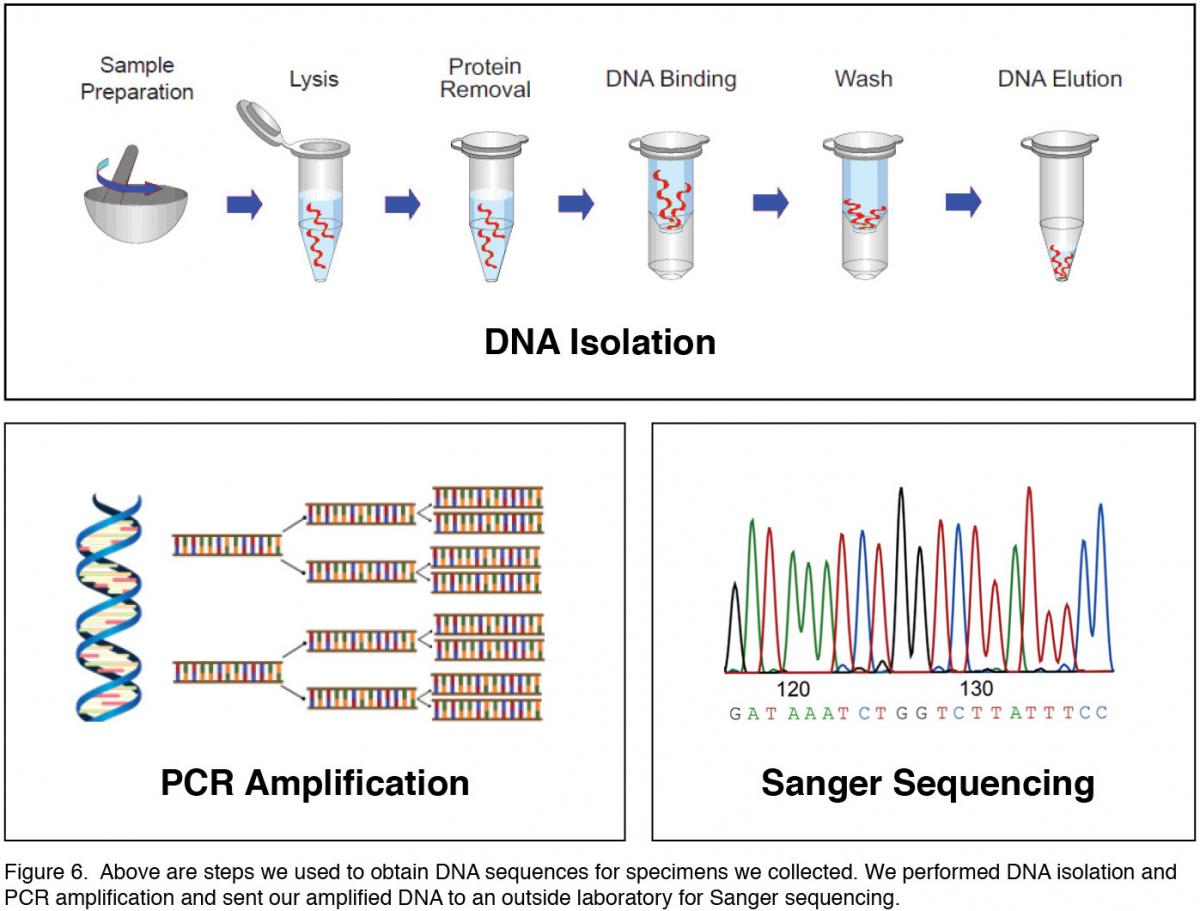

Kevin Leempoel, a postdoctoral researcher in Liz’s lab and at JRBP, then led us through the steps (Figure 6, below) of isolating DNA from tissue samples, amplifying it with PCR, sequencing a DNA fragment (CO1) used to identify animal species, and comparing sequences to those in publicly accessible databases. We successfully sequenced nine specimens and discovered to our delight that two were species yet to be sequenced. One was a soldier beetle, family Cantharidae. Its closest match in the GenBank database was Pacificanthia rotundicollis. The other was a tree damsel bug or assassin bug, family Reduviidae. Its closest match in GenBank was Himacerus apterus.

After having sent hundreds of arthropod tissue samples collected through SVBOL to be sequenced at the Canadian Centre for DNA Barcoding, we feel a sense of accomplishment to have actually completed important steps of the process ourselves. We’re very grateful to Rodolfo, Jess, Liz, Kevin, Jack, and the other people from Dirzo and Hadly labs who’ve made this possible. We admire those who’ve dedicated their lives to raising awareness about the importance of biodiversity, and to documenting it and protecting it. We’re determined to share what they’ve taught us with others so that more people will join in biodiversity conservation.

Thanks to the people in Hadly and Dirzo labs, and to Jack Owicki and other SVBOL volunteers, we’re building capacity to engage more people in collecting and processing Silicon Valley specimens for DNA barcoding. Nearly a hundred volunteers have joined us in collecting arthropods, and we look forward to working with more. We’ve also presented SVBOL to professional and civic groups, in classrooms, and at public events. If you want to participate, we’ll love to hear from you at svbarcodeoflife@gmail.com.

Kevin, the postdoctoral researcher notes that although the Hadly lab is mostly focused working on vertebrates, they are also interested in developing non-invasive tools for conservation. He states that: “molecular tools are increasingly used but require prior genetic information on the species of interest. Unfortunately, only a fraction of known species have been sequenced. For this reason, barcoding life, i.e. sequencing specimens and adding them to reference databases, is a crucial step prior to using these non-invasive genetic tools.”

If you want to learn more about SVBOL and the library of life you might visit San Diego Barcode of Life, and the International Barcode of Life. We at SVBOL and people at other biodiversity conservation organizations use Barcode of Life Data Systems (BOLD) to store and share DNA sequences and associated records. BOLD is and a wonderful resource, open to the public without charge.

A fundamental principle of ecology is that individual organisms and populations persist and thrive only to the degree that we’re well-matched to qualities of the environment we inhabit. Accelerating extirpation and extinction are evidence that the speed and quality of current environmental changes are beyond the capabilities of disappearing populations and species to accommodate. Humans, too, are subject to the mandate to adapt or perish.

We’re wondering how to contribute effectively to successful human adaptation. What shall we learn? What shall we communicate to others? How can we change to match the unprecedented speed and kinds of change in society and the larger environment? In our work with SVBOL and at JRBP we’ve taken tiny steps towards answering these questions. We look forward to evolving our responses to them as we gain experience.

Jen (left) and Hilary (right) Bayer

Palo Alto, CA