Counting Ants in Jasper Ridge

Counting ants is a study in irony and mindfulness. And why would you count them anyway? The answer lies in human curiosity and our quest to understand just what is wild. For 25 years, each spring and each fall, a dedicated group of volunteers – scientists, naturalists, and citizen scientists – has counted the ants in Jasper Ridge. They have traced the invasion of one of the tiniest members of the species, the argentine, into the preserve and watched as the native ants retreated in response. Twenty-five years of ant warfare yields unanticipated results. But first, you have to find the ants, which are ubiquitous early in the year, but in the fall their numbers fade, and one can look for hours before finding one. It is in the looking that one turns inward, absorbing the story of wild at Jasper Ridge.

The 1,200 acre preserve dedicated to studying wildness has been transected into a virtual grid of roughly 30 meter patches. Twice a year, each patch is queried for its ant population. A two-minute, nose-to-the-ground study assesses whether or not any ants appear, what kind they are, and any other notable information, which can include, for example, “saw one ant, moving too fast to identify.” On a fall day, the morning count passes pleasantly; hike a little, scout around, count, move on.

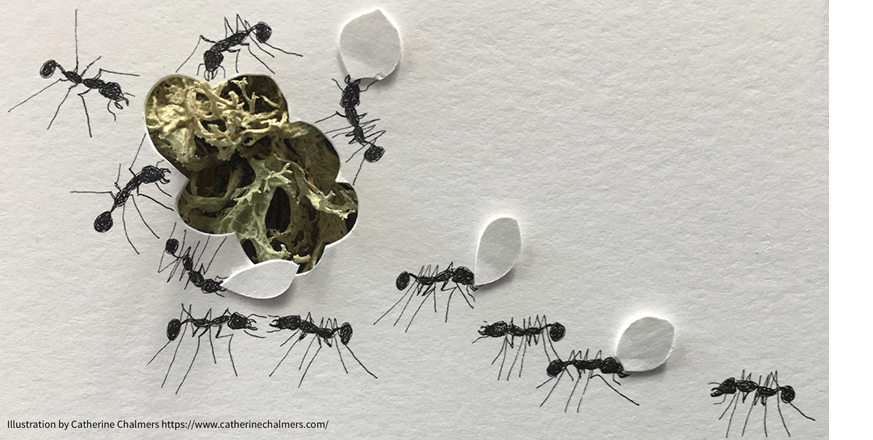

Imagine a spot on a California hill, long dry grasses around you, sticky white tarweed flowers tugging at your pants, herbal sap insinuating itself onto your legs and fingers. Serpentinite, risen over thousands of years from the molten mantle below, crumbles around you, feeding the grass. This is one of the rare fields of native grasses. Most of the golden hills of California are covered with invasive species, but here in the serpentine soil, natives thrive, adapted to the mix of heavy metals leaching from the rock. A stand of oaks graces you with shade. Over at the edge of the plot, a few rusty dried leaves clinging to sticks remind you of the misery of poison oak. A dirt trail led you here and presented a perfectly round hole alive with ants carrying grains, grasses, each other, dipping in and out of their hole, traversing the debris pile of inedible roughage they have rejected. But not one of these harvester ants seems to have any interest in your little plot. Shiny and black, following each other around, they would be easy to spot – if they were there.

If you’re lucky, you might move to the next plot and inspect that oak tree closely and notice sun glinting off a moving dot. Study it for a few moments and you’ll see a trail of tiny ants. Argentine. These are the ants who swarm into your house in winter. Ferocious, they take no prisoners – over 25 years they have taken over whole areas of Jasper Ridge, driving out native species and claiming the ground as their own. But not all of it. They stick to the wetter areas, and the borders that abut neighborhoods, easy marks for the winter invasions.

Of equal interest are the people gathered to survey the ants. A mish-mash of people studying ants for a living, ecologists, naturalists, retired professors, and curious neighbors. Crouching over a nest, or a trail, or a single ant, they lick their fingers and gently touch the back of a scurrying ant, then pinch its legs to get a better look. My amateur classification system – big, little, red, black – is of no use. I struggle to apply my crash-course in ant identification. Some ants come in two sizes. Some are dusty. But hold an ant by its legs and you can look at the slope of its shoulders, see the shape of its head, examine the angle at which its abdomen stands, and declare this one a field ant, that one a harvester. Once you have identified it, roll the ant between your fingers, or brush it off on your pants. An ant is like a cell in the body – one more or less is of little consequence. This is the first team of naturalists I have encountered that simultaneously reveres their subjects en masse yet disdains the individual.

Walking through the fields, we come across carpenter ant trails. An inch or two wide, the trails crisscross the ground, devoid of any kind of growth – bare dirt made so by the industrious glossy black ants, huge in comparison to their argentine cousins. Carpenter nests are holes in the ground, really big holes, and at this time of year, they are teeming with ants as the new queens fly off for their nuptial dance and honeymoon to their very own new nest. Blue jays roost in nearby trees, ready to snap up the treats as they fly by.

Survey complete, we wander down from the field station, built of recycled materials, inlaid with solar panels, surrounded by bricks that came from Scotland as ballast, briefly formed a house, and now return to the ground as a sun-soaked playground for rattlesnakes, leaving the valley oaks and heading into scrub oaks and blue oaks, bay laurels and poison oak. We rest a moment in the shade, looking up a grassy hill, hawks shrieking in the distance. At our feet is a wildlife camera, solar-powered, streaming to the cloud. Over 200,000 images have been captured by this camera and its brothers. Images of bobcats and rabbits, coyote and mountain lions. Raccoons, skunks, squirrels, snakes. And people; a lot of people.

Jasper Ridge aims to be wild, or to define it, but dirt roads and a dammed up lake; single-engine planes overhead and the constant muffled roar of the freeway; wafts of sunscreen and Tecnu – none of these speaks to me of the wild. They infringe on my senses, drawing me away from nature. It takes work to be wild, and I look hard for a space where I can breathe, lose myself, and sink into reverie.

I find my space between three forked oaks. A flat circle covered in leaves, dappled light filtering through the boughs, skimming off the mossy trunks. Up in the limbs, rough-edged leathery leaves stand against the sky, defying the sun and the dust and the months of rain-free days. A hawk screams. Leaves whisper. Tracing a limb up toward the sky, I see a clump of leaves – a nest? Or the by-product of a snag that rests there? Brown leaves against green, the dead limb hangs at an odd angle; it must be a foot across, caught there in last year’s storms, ragged stump dangling free. It was not a clean break. The other end of it, on a still-living tree, is ten feet away, raw, ripped, tree-flesh fraying upwards.

I picture the night-storm, the rain, the wind like a demon sliding through the woods, sucking air behind it, rising to a howl and fading, rising and fading, picking at the forest, demanding action, cracking twigs and blowing curls of dead leaves until finally, one gust, one heavy drench of rain, snaps the limb and it careens across my glen, landing in the neighboring tree with a rush and a calm. A spidery froth sits now on the torn end. And perhaps that is a squirrel nest, tucked in where the snag rests against moss.

What is wild? Is it here, a biodiversity hotspot filled with interdependent flora and fauna, each doing its job, pushing other species around and demanding a niche? We know they are here because they are the subject of endless observation and images, studies set up for us to interpret. Are they wild before we photograph them, or because we do?

Hawks scream and a woodpecker flies by, chattering in a nearby tree, stashing acorns in the rows of holes drilled into the dead wood. Behind it, a constant white noise emanates from the nearby freeway. I walk past the camera and imagine my likeness riding an electromagnetic wave to the cloud, showing up on a distant screen where I can be counted too.

Sofie Kleppner is the Associate Dean for Postdoctoral Affairs at Stanford. She wrote this piece as part of her coursework in ‘Nature Writing at Jasper Ridge,’ a Stanford Continuing Studies class (WSP 70) taught by Lynn Stegner.