Natural History Note: Camera trapping reveals the impact of fuel reduction on woodrat nesting behavior

An image of two dusky-footed woodrats captured at night by a camera trap.

During the fall of 2023, a required fuel reduction treatment was conducted at Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve (‘Ootchamin ‘Ooyakma) along the Westridge fence line to create a fuel break that helps mitigate wildfire risk for the preserve and neighboring properties. Most of the reduction was within 300 feet of the fence where a species of concern is known to inhabit the oak woodland area. The San Francisco dusky-footed woodrat (Neotoma fuscipes ssp. annectens) is a small, nocturnal, arboreal mammal that is generally selective for suitable habitat based largely on food and protection. The impacts of fuel reduction on the woodrats were not understood, so a docent-led project was conducted by Bill Gomez to detect the presence of woodrats at nests using camera traps.

Figure 1. Woodrats have small ears in proportion to their body size (see image left). A female woodrat and a juvenile woodrat (image right). Images taken by a camera trap; credit Bill Gomez.

Because woodrat habitat usually changes slowly over time, woodrats have low reproductive rates, and woodrats do not often build new nests, the population of woodrats can be stable. This raised the question of how woodrats would be impacted by fuel reduction treatments.

The dusky-footed woodrats create intricate nests from woody vegetation (Fig. 1). Woodrats will only move into houses in good repair, and in two years of observation at Jasper Ridge, only 2 or 3 small new houses have been seen under construction at Mapache and Escobar monitoring areas. This is in line with previous findings by Linsdale and Tevis, 1951.

Shrubs in the nest area provide cover from predation, building materials for nests, and food sources. Woodrats were previously found to often avoid traveling directly on the ground, which may reduce predation (Linsdale and Tevis 1951). They travel on above-ground limbs at least three inches in diameter or logs and large limbs on the ground.

Most woodrats (70%) live a year or less, but they can live up to four years (Linsdale and Tevis 1951). Female woodrats move to a new nest with each new litter, and since young tend to stay in the maternal house for some time, this reduces the risk of finding a new home, ultimately enhancing survival.

Fuel reduction at Jasper Ridge took place in September 2023 and consisted of crews using chainsaws to remove lower branches of mature trees which removed “fuel ladders” as well as removing small trees and shrubs, which reduced fuel load at ground level (Fig. 2). Materials were then chipped and broadcasted in the area.

Figure 2. A woodrat nest before and after fuel reduction. Photos by Bill Gomez.

In the fuel reduction areas around Mapache and Escobar gates, woodrat nests were flagged and a buffer of about a 5-foot radius from nests was not treated by the crews. Motion detecting cameras were placed near woodrat nests and pointed at the entrances of the nests for 6-14 day periods. Camera footage was captured in the month before fuel reduction, in the month after fuel reduction, and nine months thereafter, to determine the impact of fuel reduction on woodrat nesting behavior.

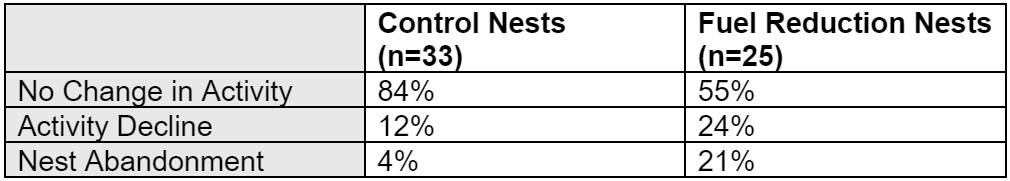

All nests studied were occupied by woodrats prior to fuel reduction. A total of 58 nests were monitored over the course of 10 months, comprising 33 nests in fuel reduction areas and 25 nests outside the reduction area, which served as a control group.

The woodrats experienced disturbance during fuel reduction, and they abandoned one-fifth of nests, while infrequently visiting almost a quarter of other nests (Table 1). In time, the woodrats reinhabited over half of these abandoned nests, suggesting that fuel reduction impacts on the occupation of nests may be temporary. Additional disturbance within this reoccupation period may have deterred the woodrats from returning to abandoned nests, but experimentation is needed to confirm.

When woodrats entered or left their nests, motion-detecting cameras captured images, and these images were used to quantify nest activity (Fig. 1). The following table shows the impact of fuel reduction treatments on nest activity, quantifying the percent change in activity within one month after fuel reduction. The category “No change in activity” describes nests that remained with the same level of activity before and after fuel reduction treatment (e.g., if highly active before, they remained highly active thereafter). Activity decline indicates nests which were originally found to be highly active then were found with low activity after fuel reduction treatment. Low activity at a nest indicates fewer than five woodrat images were captured per imaging period. Nest abandonment indicates nests which were originally inhabited by woodrats then no woodrat activity was detected after fuel reduction.

Table 1. Change in nest activity one-month after fuel reduction (September 2023).

Using a chi-squared test, the results in the table show a statistically significant difference between controls and fuel reduction with a p value <.05.

Approximately nine months after fuel reduction (June-July 2024), all nests were re-monitored for woodrat activity. These data showed that 13 nests (52%) in the fuel reduction group changed from low occupancy or abandonment to very active. Only 4 controls (12%) showed that change. In the nine-month period, adult or dispersing young woodrats reoccupied some nests in the fuel reduction area. Since woodrats are known to move fairly frequently between nests and young woodrats disperse, these results are perhaps not surprising. This study reveals that many nests were reinhabited within a nine-month period after disturbance.

These results may be specific to fuel reduction in oak woodland habitats, which comprise the areas around Mapache and Escobar gates. Future work could investigate the effects of disturbance in chaparral or riparian habitats where the density of nests is lower and higher, respectively.

Several areas of fuel reduction along the Westridge fence line had substantially more fuel reduction activities than this study’s sites, including mastication treatment. The conclusions of this study do not apply to woodrat populations in areas that underwent different treatments. Additionally, this study is the first of its kind at Jasper Ridge, and it serves as an important baseline to continue learning about the long-term effects of fuel reduction on woodrat populations.

Acknowledgements from Bill:

Thank you to Liz Hadly, Tony Barnosky, and Nona Chiariello for encouraging me to study woodrat responses to fuel reduction; Tad Fukami and Adriana Hernandez for reviewing and commenting on my reports; Steve Gomez for securing project supplies and field support.

Funding

All supplies for this project were purchased with Jasper Ridge funds under a new Fire Abatement effort created by Jorge Ramos with support from the School of Humanities and Sciences. With JRBP funds, Sheena Sidhu purchased 10 cameras, and Steve Gomez purchased approximately 70 tee stakes for mounting cameras at nest sites.

Reference

Lindsdale, J.M., & Tevis, L. P. (1951). The Dusky-Footed Wood Rat: A Record of Observations Made on the Hastings Natural History Reservation (1st ed.). University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.8085412

Written by: Bill Gomez and Adriana Hernandez, Ph.D.

Bill Gomez retired over 30 years ago to pursue volunteer environmental education opportunities. He has been a docent at Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve since 1996, focusing on both leading tours and aiding research projects.

Bill Gomez retired over 30 years ago to pursue volunteer environmental education opportunities. He has been a docent at Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve since 1996, focusing on both leading tours and aiding research projects.

Adriana is the Assoc. Director of Research at Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve. Adriana's passion for biodiversity studies, collections-based research, and natural history has driven her to a research career in plant and evolutionary biology and conservation. Read about her background here.

Adriana is the Assoc. Director of Research at Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve. Adriana's passion for biodiversity studies, collections-based research, and natural history has driven her to a research career in plant and evolutionary biology and conservation. Read about her background here.