Music of the Spheres: Hearing the Anthropocene in Searsville Reservoir Sediment Cores

Pythagorus once proposed that sun, moon, stars, and Earth make a harmonious universe of sound called the music of the spheres. Contemporary earth system science confirms that spheres make our planet function. Not by divine music, however, but in a complex interplay among the atmosphere, the hydrosphere, the lithosphere (geology) and the biosphere.

Today the interactions among these spheres are changing at an unprecedented pace. Human activities are transforming landscapes and changing the chemical and biological fabric of the Earth. Profound global impacts can be discerned in the fossil record and herald a new geological epoch. We no longer reside in the Holocene but are participants in the redoubtable Anthropocene. How did this happen, what does it mean, and how can we address our newly recognized power to alter planetary boundaries?

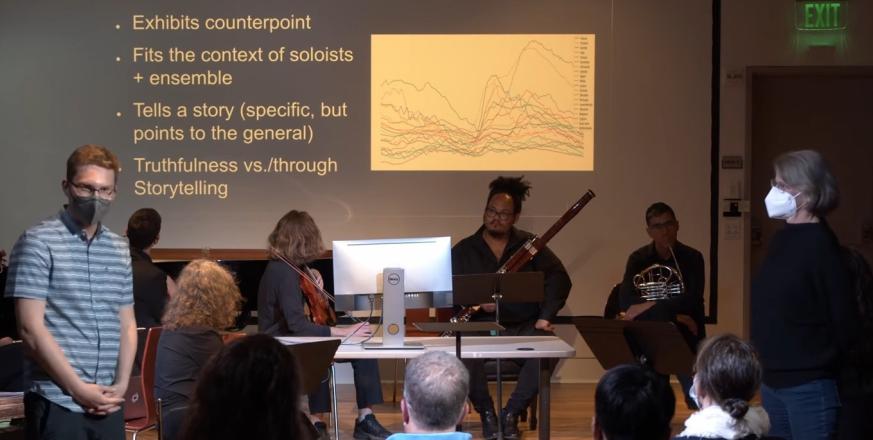

CT-scan (left) and line scan (right) of part of a sediment core from Searsville Reservoir.

Allison Stegner and collaborators from the United States Geological Survey obtained the cores as part of an international project to determine when the Anthropocene began, and how to define it for the geological time scale.

Sediment cores from Searsville Reservoir have been studied for the past four years to try to figure out the answer to the question. And now, you can actually listen to what the cores tell us, thanks to a collaboration between JRBP researchers Elizabeth Hadly and Allison Stegner with musician Marc Evanstein. Together the trio transformed data from the cores into a musical score, through a process that emphasized expressing the hard facts of science through a filter of human perceptions and experience. The result premiered on stage at Stanford’s Center of Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) at the end of the Spring 2022 quarter.

Hadly and Stegner are currently investigating chemical and biological signals of change over time at Searsville Lake on Stanford’s Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve. With colleagues they have extracted sediment cores to parse out exactly what happened here, and when, as part of an international project to formally define the Anthropocene. The timeline they are constructing sheds light on how human activities are impacting Earth processes.

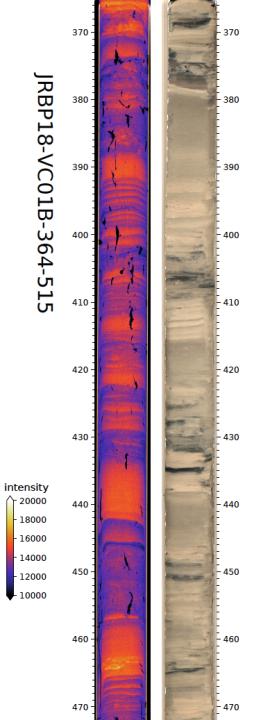

Composer Marc Evanstein has long transformed scientific and mathematical data into music, by way of a set of tools he developed in the Python programming language. Of the myriad data sets discerned from Searsville sediment, the trio focused in on pollen to dramatize the constantly shifting balance of tree species over time. These species are given voice by the soloists, while the larger ensemble provides a backdrop based on an analysis of the core density, which reflects weather patterns and other abiotic elements.

Hadly’s Lab of the Anthropocene at Stanford is focused on traditional scientific methods, yet also seeks to more broadly embrace the full spectrum of the liberal arts to understand what is happening to the trajectory of life on Earth and why. Our personal and cultural orientation to reality is challenged by the complexities of the multivalent Anthropocene. Mapping Hadly and Stegner’s data to music, Evanstein says, provides an “opportunity to hear the intricate dance by which different factors in an ecosystem, and in our world as a whole, play off one another.”

To help bridge the distance between science and art, Hadly and Stegner provided not just pollen data, but more emotionally-imbued adjectives supplied by docents at Jasper Ridge. The docents have empirical knowledge of its iconic California landscape but also personal associations with the tree species there. Douglas fir is “mighty,” “powerful,” and “companionable.” Willow is “whispering,” “rustling,” and “sighing.” Evanstein referred to the docents’ adjectives to characterize species in musical phrases, in turn largely shaped by the computer using probabilities that reflect patterns in the pollen.

Translating data to music.

The pollen data indicate that construction of Searsville Dam in 1892 caused a large delta to form, instigating a succession of White alder (Alnus rhombifolia), which was then replaced by willow (Salix). Sequoia (Sequoia sempervirens) and Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) were vastly reduced by logging in the 1880s, and later recovered. Iconic Oak (Quercus) made a similar comeback once grazing was restricted at Jasper Ridge. These changes over time are expressed by the music. “There’s a point that’s pretty dramatic here – where the willow starts to recover, with little oak gestures in the middle.”

One thing Pythagorus got right: myriad parts of nature are connected with each other across time and space, in constant motion, instigating feedback mechanisms among parts of the whole. Like the music of the spheres, the Anthropocene is a transcendent, immersive state of change. While humanity has set much destruction in motion, deeper resonance with nature’s inmost workings may help us recast our role in this narrative. As Hadly, Stegner, and Evanstein make abundantly audible, beautiful harmonies can coexist.

Mary Ellen Hannibal serves on the Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve Coordinating Council. She is an award-winning author (Citizen Scientist: Searching for Heroes and Hope in an Age of Extinction; The Spine of the Continent) whose work has also appeared in Bay Nature, The San Francisco Chronicle, The New York Times, and many other publications.