Summer interns help unlock the mysteries of Jasper Ridge's migratory birds

Julian Tattoni, the founder of the Jasper Ridge bird-banding station, gives a Swainson’s Thrush its Motus backpack. Photos by Trevor Hebert and Marty Freeland.

If you see a Swainson’s Thrush (Catharus ustulatus) wearing a little backpack with an antenna at Jasper Ridge, don’t be alarmed—as hard as it may be to believe your eyes, the bird isn’t a robot spy, and you’re not hallucinating! It’s just the newest development in Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve ('Ootchamin 'Ooyakma)’s bird-banding and monitoring program.

This summer, backpacks for birds has been the goal of a small team coordinated by Trevor Hebert, enlisting the help of our fantastic banding partners at SFBBO and beyond—especially Julian Tattoni and Katie LaBarbera—and including BSURP interns Noah Macias and myself, as well as SOAR intern Maya Xu. They’re not just any backpacks, though. These are Motus tags, and with luck they will be able to shed some light on the mysteries of Swainson’s Thrush migration.

Every year, Swainson’s Thrushes make their way to ‘Ootchamin ‘Ooyakma in late April or early May and consider it home until September. They nest in the large tract of mature riparian woodland at the southern end of Searsville Lake and are often heard, and regularly seen, around Leonard’s Bridge. Their distinctive flute-like song is among the most beautiful bird sounds at the Preserve in spring and summer. But from October to March they leave the United States entirely, traveling as far as 5,500 miles away to winter in the rainforests of Central and South America.

But the details of their extraordinary migration remain very poorly understood. How many stopovers do they make along the way, if any? How long does the journey take? And where exactly do our birds winter? This species’ non-breeding range is quite broad, spanning suitable habitat from Mexico to northern Argentina, and we have absolutely no sense of where within that vast area the birds from Jasper Ridge are spending the winter.

These are important questions not only because they are interesting—though they are indeed fascinating in themselves!—but also because they offer insight into the conservation needs of this species and of the other Nearctic-Neotropical migrants that can be found at Jasper Ridge. (Western Wood-Pewee and Wilson’s Warbler are two other examples.) Although these birds are well protected for the time being at Jasper Ridge, it is of course vital to understand the entirety of their annual cycles in order to get a sense of what kinds of threats they may face at stopover and wintering sites. With that more complete picture in mind, we are better equipped to try to halt or reverse the steep declines that most long-distance migratory birds are experiencing across their ranges.

Swainson’s Thrush is an ideal case study for clearing up some of these questions because, for one thing, they are caught frequently at the Jasper Ridge banding station—and for another, they are rather large compared to most of our other migratory passerines. This is essential because only birds of a certain size are able to carry our Motus backpacks.

Comparing the sizes of Swainson’s Thrush and Wilson’s Warbler in the hand. Photos by Trevor Hebert and Marty Freeland.

The Motus system itself is a truly amazing development in the realm of tracking and understanding bird migration, which has come a long way since the days of Aristotle when migratory birds were thought to hide in riverbed mud or transmute into shellfish during the winter! Motus technology allows us to track birds across continents without having to recapture them to download data from GPS devices (a key sticking point for many previous tracking studies) and without spending thousands of dollars on each individual transmitter.

Instead, when a Motus tag is attached to a bird by means of a lightweight backpack setup, it begins emitting radio pings that register with special receiver stations from as much as 20 kilometers away. The tags can recharge themselves by means of a miniature solar panel embedded in the mechanism, so they never run out of battery and their signals never stop. Since each tag has a unique signature and receivers are distributed across the landscape from California to Argentina, it should be possible to pick up signals from the tagged thrushes at multiple points along their migratory route and hopefully on their wintering grounds as well.

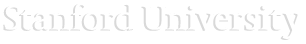

You can keep up to date on all eight (and counting!) tagged Swainson’s Thrushes—and see our other Motus records too, like the Band-tailed Pigeon tagged elsewhere by California’s Department of Fish and Wildlife that flew over Jasper Ridge!—on the Jasper Ridge Motus page, where records from our receiver station are displayed almost in real time. JRBP'O'O joined the 2,000+ stations of the Motus collaborative research network when we installed our receiver station in May of 2024.

The Motus station at Jasper Ridge overlooking the riparian woodland. Photo by Trevor Hebert.

The process of catching Swainson’s Thrushes in mist nets early in the morning and giving them their Motus backpacks is an educational tool as well. The experience of holding a bird in your hand and helping to give it a backpack full of cutting-edge technology to unravel the mysteries of its migration is powerful for anyone, really, but especially for those with less background in fieldwork and ecological research. We’ve had opportunities to share these experiences with youth from the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe, the family of Jasper Ridge staff and affiliates, and anyone else who happens to come by Leonard’s Bridge on a bird-banding morning.

And even though only thrushes are large and strong enough to carry the Motus tags, we certainly do catch other birds as well in the course of banding operations. For them, we do just what Julian Tattoni has been doing ever since they opened the banding station in 2018: we measure them, take information on demographics and body condition (especially molt), and then let them go with a tiny metal ankle bracelet with a unique number that serves as an identifier should the bird ever happen to be caught again, here or anywhere else.

For Noah and myself, Motus tagging with Swainson’s Thrushes has certainly been the highlight of our summer research here at Jasper Ridge! Our other projects, like Noah’s waterbird research and my new JRBP('O'O) bird checklist, have been fascinating as well—but nothing compares to holding a bird in your hand and then letting it fly off, bound for South America, carrying your miniature research devices on its back.

An Oak Titmouse, captured during banding operations, chews on the finger of BSURP intern Marty Freeland. Photo by Trevor Hebert.

Marty is a rising sophomore in the Dirzo Lab (Dept. of Biology), originally from the San Francisco Bay Area. He studies everything about birds but focuses especially on their movement patterns, and on the weekends you can find him scouring coastal creeks for vagrants—which are basically birds that get lost.

Marty is a rising sophomore in the Dirzo Lab (Dept. of Biology), originally from the San Francisco Bay Area. He studies everything about birds but focuses especially on their movement patterns, and on the weekends you can find him scouring coastal creeks for vagrants—which are basically birds that get lost.

Noah is a rising senior in the Earth Systems program following the Biosphere track and is from Oak Cliff in Dallas, Texas. Noah is interested in a career in sustainable food systems with a focus on native edible plants. You’ll most likely find them in a creek enjoying the ambience and observing all aspects of the ecosystem.

Noah is a rising senior in the Earth Systems program following the Biosphere track and is from Oak Cliff in Dallas, Texas. Noah is interested in a career in sustainable food systems with a focus on native edible plants. You’ll most likely find them in a creek enjoying the ambience and observing all aspects of the ecosystem.