Tracking the Aquatic Insects of Jasper Ridge: Remote Science During a Pandemic

In the age of COVID-19, scientific research is something that has been put on hold for many. This project was a testament to remote research and the ability to still participate in meaningful science during nation-wide shelter in place. After my original summer program was put on hold due to COVID-19, I was able to work with Allison Stegner to create a new project that could be done remotely. It was based off a new and pressing issue in the world of biology.

The inspiration for this project comes from a conservation issue that has recently gained a large amount of attention, informally known as the “Insect Apocalypse.” In many parts of the world, insect biomass is severely declining, and scientists are struggling to figure out why. One major obstacle they have run into is a lack of data on insect populations worldwide. It is impossible to measure a decline in insects if there is no data on how many there were in the first place. Despite the current data limitations, you can notice it whenever you merely go outside. Drive down a rural highway and you may notice fewer bugs on your windshield than when you were younger. But Stanford’s own Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve is an exception to the data deficiency. Jasper Ridge maintains a man-made lake (Searsville Lake) and a natural sag pond (Upper Lake) which gives access to sediment cores containing aquatic insect remains and DNA (Fig. 1). These cores will allow us to go back in time and measure insect diversity, and hopefully, the size of these populations, to follow how they have changed over decades and centuries.

Figure 1. Searsville Lake in October of 2020 at Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve (Photo by Jorge Ramos)

But before any analysis can take place, it was necessary to establish what species live in the Jasper Ridge area and in the surrounding Santa Cruz Mountains. My project consisted of building a database of all species of mosquito (Family: Culicidae), damselfly and dragonfly (both of Order: Odonata) native to the Bay Area (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Examples of mosquito, damselfly and dragonfly (photos by Jack Owicki)

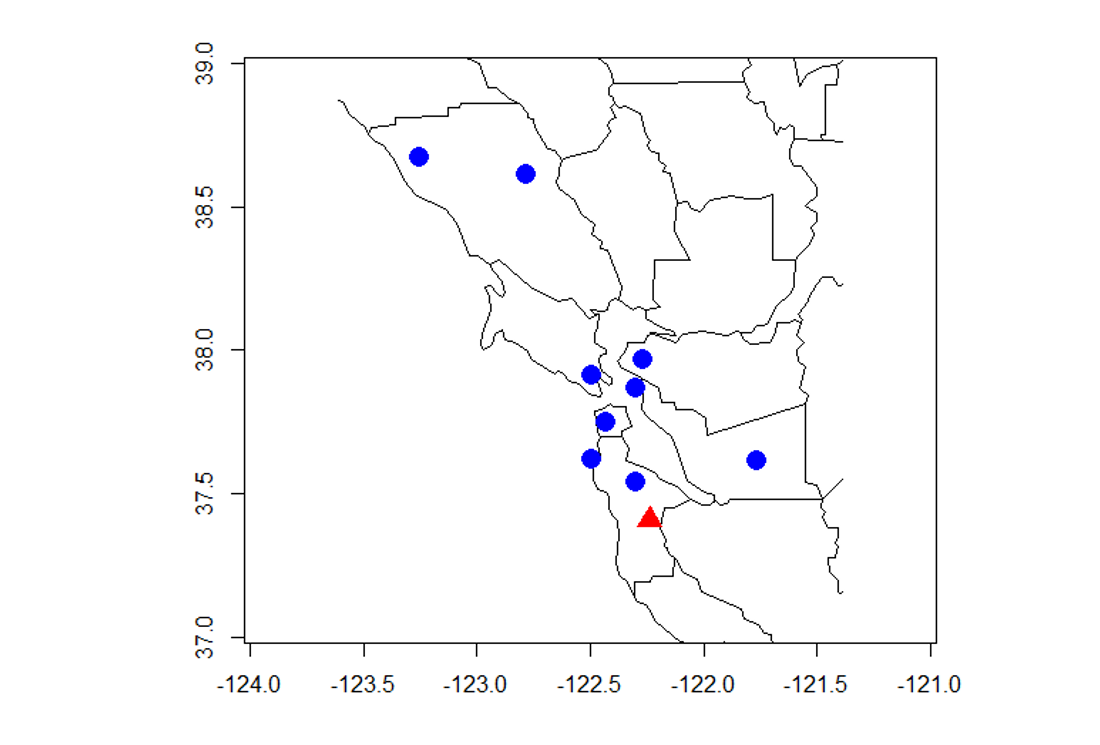

These groups of insects spend most of their lives in and around water making them perfect candidates for measuring the insect biomass in the Searsville Lake cores. Because this was impossible to do in person at the time, I used a variety of online resources to build the database. Sightings were taken from the online naturalist site Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) (Fig. 3). GBIF includes data from iNaturalist, a resource that allows naturalists of all skill levels to post and identify their sightings of species in any given area. I was able to search for all members of the family Culicidae and order Odonata present in the Bay Area (Fig. 4). In addition to the names of the species, there were also corresponding longitude and latitude coordinates for almost all sightings in the GBIF data, which allowed me to build maps, like the one shown here. All maps were created using the statistical analysis software R v. 3.6.3.

Figure 3. Global Biodiversity Information Facility interface (https://www.gbif.org/).

Figure 4. An enhanced map of the sightings of the mosquito species Culex tarsalis (blue dot) in the respective Bay Area counties with Jasper Ridge (red triangle) as a geographic reference.

Other online sources outside of GBIF were also necessary in order to build a comprehensive list of the species present in the Jasper Ridge area. These sources included peer reviewed articles, county vector control websites, and wildlife databases (examples [1], [2], [3]). I was also able to secure the help of a member of the San Mateo County Mosquito & Vector Control District who assisted me with building an accurate database for the mosquitoes of the area. I was amazed to learn that 29 species of mosquito and 119 species of Odonata (dragonflies and damselflies) call the Bay Area home. Two of these species are the mosquitoes Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, both of which are invasive species spread Zika virus and yellow fever. These are the most common mosquitoes in the world, having made their way to every continent except Antarctica. Small populations pop every so often in the Bay Area, but according to the San Mateo County Mosquito & Vector Control District, all have been wiped from the region.

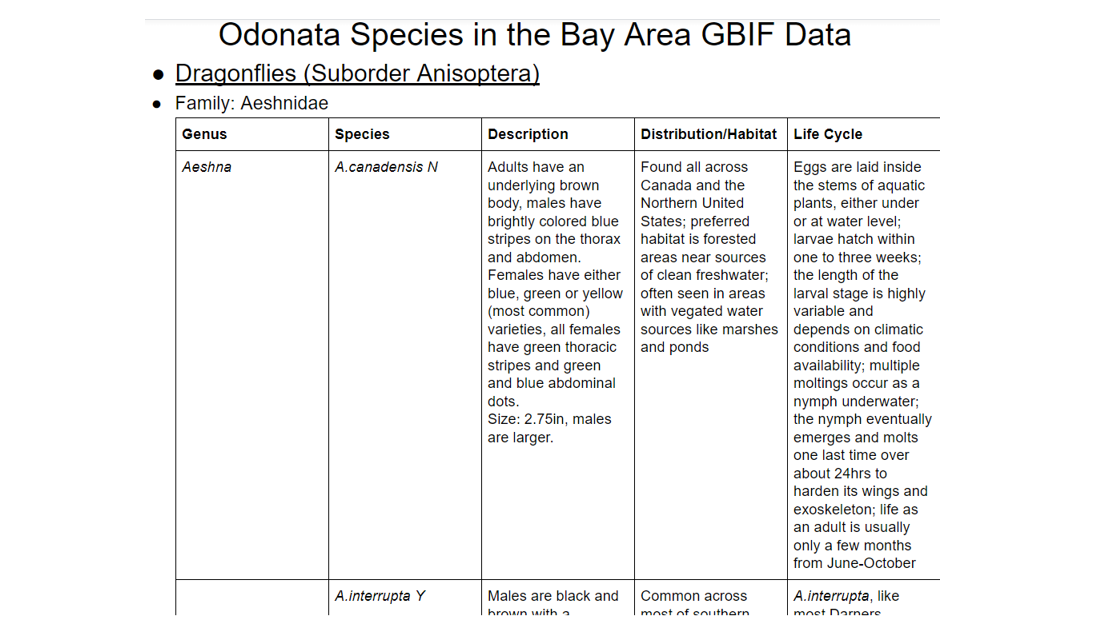

For the database, I created two similar trait tables with the defining features of each species: one table for the mosquitoes and the other for the dragonflies and damselflies (Fig. 5). The tables contained slightly different categories of traits, for instance, the mosquito table mentioned which disease each species carries, while the other table did not. These databases will help Jasper Ridge and other regional researchers in identifying and understanding the species which could be discovered in the Searsville and Upper Lake cores.

Figure 5. Example of the Odonata table with respective traits for a dragonfly species.

The creation of these databases presented a new kind of challenge for me as a scientific researcher. Not being able to do hands-on work and being away from my mentors, Elizabeth Hadly and Allison Stegner, forced me to do something outside the normal, as was the case for many students participating in summer research. But I am grateful that I was able to be a part of the first steps in understanding the insect populations in the cores from Jasper Ridge. I am also excited that this research can be applied to the greater Jasper Ridge community. I believe there is important scientific work to be done here and great potential for adding to the community studying the “Insect Apocalypse.” This work is still ongoing, and although COVID-19 has created some challenges, I am hopeful that there will be much good to come.

Zack participated in the Biology Summer Undergraduate Research Program (B-SURP) program and worked with Dr. Allison Stegner and Dr. Elizabeth Hadly.

To read Zack’s final project, please download his B-SURP research poster.

Zack LaGrange, is a Stanford undergraduate student (class of 2021) majoring in Biology with a minor in Classics.

Zack LaGrange, is a Stanford undergraduate student (class of 2021) majoring in Biology with a minor in Classics.