Oakmead Herbarium: floral postcards

2024 Quarry off Trail 12

- Plant list

- Dirca planting by docent class 3/2024

2023 Invasive Alien Species Assessment

- Invasive Alien Species Pose Major Global Threats to Nature, Economies, Food Security and Human Health

- Key Role in 60% of Global Plant & Animal Extinctions

- Annual Costs Now >$423 Billion – Have Quadrupled Every Decade Since 1970

- Report Provides Evidence, Tools & Options to Help Governments Achieve Ambitious New Global Goal on Invasive Alien Species

See below "The Preserve at 40" (Stanford Report), "Invasion of Serpentine prairie by nonnative grasses", "Winter walking along San Francisquito Creek"

Leptosiphon parviflorus color morphs

Sudden Oak Death (SOD)

We have been monitoring for SOD annually at Jasper Ridge since 2008 via the SOD Blitz operated by Matteo Garbelotto (it’s a citizen science activity). The survey involves sampling symptomatic leaves from California Bay, which is the main reservoir for the pathogen. The Garbelotto lab then tests the leaves.

The sampling has expanded somewhat over the years at Jasper Ridge, but for the most part we sample the same trees every year (this year it was nearly 50 Bay trees). The first SOD-positives at Jasper Ridge were in 2012, and in most years since, there have been a few positives.

The SOD Blitz website provides a kmz file of cumulative results across their entire survey; map showing those results for Stanford/JRBP and the surroundings, with the boundaries marked for Stanford (white) and JRBP (yellow). The results of the 2023 survey will be available in Sept or October. The map suggests that very little SOD Blitz sampling has been done on Stanford lands other than Jasper Ridge.

At Jasper Ridge, a number of Coast Live Oak trees have died that had classic SOD symptoms and were near Bay trees whose leaves had tested positive for Phytophthora ramorum. For some people that might not be conclusive enough regarding SOD presence and disease impacts, but at minimum, it is very strong evidence. (Nona Chiariello, Aug 15, 2023)

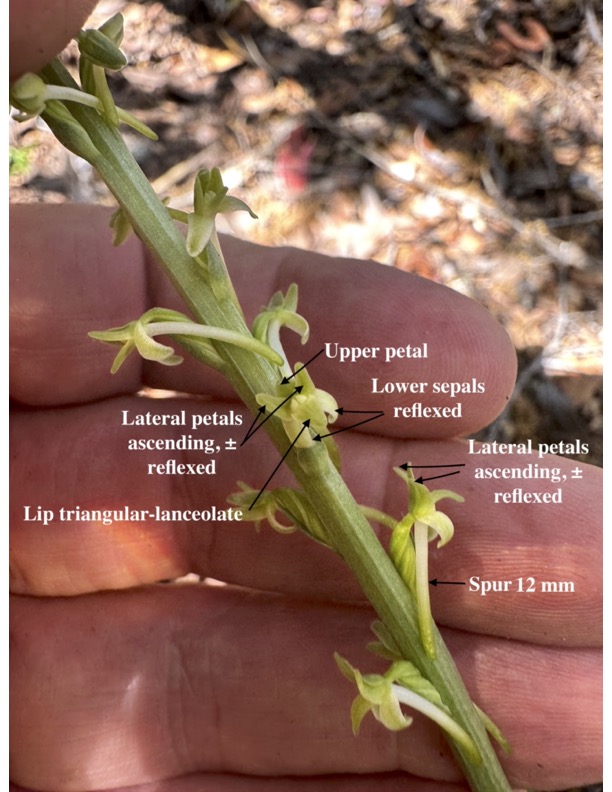

7/2/2023 New orchid documented for Preserve

Piperia elongata -- Calflora | iNat (better

Basal lvs spotted by Mary Bernstein 2/21/2023. Identification made when flowering 7/2/2023

Compare to the similar Michael's rein orchard (Piperia michaelii) relocated 6/27/23 along Rd F. Plants lost to herbivory -- stems chewed off -- by 7/2/23

6/28/2023 Eryngium jepsonii [Rank 1B.2]

Jasper Ridge Preserve and locality have almost 50 years of observations and a century of voucher records for this unusual member of the Carrot Family and special status plant. Yet the most extensive local occurrence, far exceeding the density of other patches, many hundreds of flowering individuals in closely spaced dense patches, was only recently reported north of Trail 15 at the Serpentinite/Whiskey Hill Sandstone contact (iNat record photos). Seemingly another artifact of the heavy rainfall this season and the Herbarium group's exploration of microhabitats.

2023: New plants and relocated plants

- Isoetes nuttallii iNat (better

photos), Calflora [See iNat records for discussion] - Isoetes howellii iNat (better

photos), Calflora [See iNat records for discussion] - Ranunculus pusillus iNat (better

photos), Calflora - Piperia elongata Calflora | iNat (better

photos) - Ricinus communis Calflora [Removed]

Relocated plants

- Calamagrostis rubescens Calflora [First record of flowering individuals since 1980]

- Piperia michaelii Calflora [Two flowering individuals Along Rd F near Trail 15, most recently recorded over a decade ago. The orchid is a special status plant [CNPS Rank 4.2]

- Triglochin scilloides (Lilaea s.) iNat (better

photos), Calflora [Semaphore grass depression (aka Pond A) as well as in the Boething marsh] - Xanthium spinosum Calflora

New locs for locally rare and watchlist plants (aka special status, locally rare and watchlist)

- Allium spp.

- Cuscuta subinclusa Calflora

- Epilobium torreyi Calflora, iNat

- Eryngium jepsonii Calflora [largest known occurence]

- Senecio aronicoides Calflora [largest known occurence]

- Helianthella californica californica Calflora

- Navarettia mellita Calflora

- Pentachaeta alsinoides Calflora

- Tauschia hartwegii Calflora [only known serpentine occurence]

- Rhinotropis californica Calflora [largest known occurence]

- Malacothamnus arcuatus (RANK 1B.2) iNat [outside of Preserve near southern boundary]

- Hetercodon rariflorum Calflora [largest known occurence]

- Zeltnera davyi Calflora [largest known occurence]

Historical vouchers: Redwood understory plants not relocated on the Preserve

- California sweetgrass, 1867 "Redwoods, Searsville." Source of the group's sweet smell: "The fragrance emitted when fresh plants are crushed or burned is from coumarin. In addition to smelling pleasant, coumarin has anti-coagulant properties. It is the active ingredient in Coumadin, a prescription drug used to prevent blood clots in some patients after surgery." (FNA: 24)

- Redwood sorrel, 1915 (earliest record 1895) "Searsville"

- Slink pod, 1867 "Searsville"

- Two-eyed violet, 1972 (earliest record 1893) "redwood grove by Searsville Rocks"

- Five-finger fern, 1983 (earliest record 1965) "Water seep around the dam keeps the franciscan rock wet"

2023: Berberis

2023: Current and Historic Willow Forest of the Searsville Area

2023: JRBP Piperia, terrestrial orchids, 2/21/2023

2023: JRBP Allium, 2/14/2023

2022: Helianthella californica californica [Locally Rare]

2022: Quercus palmeri [Locally Rare]

2022: Dichelostemma multiflorum [Locally Rare]

2022: Malacothamnus arcuatus (RANK 1B.2)

JROH specimens were on loan to RSA for a few years. Morse writes, "Re Malacothamnus fasciculatus var. fasciculatus: Plants from Jasper Ridge are M. arcuatus. This taxon was not recognized (even as a synonym) by Tracy Slotta, but is recognized by CNPS and, based on my current research, will probably be recognized in future treatments. M. fasciculatus is not known to naturally occur north of Santa Barbara County." Presentation for the PhD defense of Keir Morse in 2022:

Abstract: Malacothamnus (Malvaceae) is a genus of fire-following shrubs found primarily in the California Floristic Province. The taxonomy of the genus has been controversial for many years due to conflicting treatments, which recognize between 11 and 28 taxa. Many taxa of conservation concern are not recognized in some of these treatments, which makes resolving taxonomic questions in the genus a conservation priority. To resolve these questions, I use a combination of morphological, geographic, and phylogenetic evidence. Morphological analyses are first used to test and refine previously published and novel hypotheses of taxon boundaries within the genus that are based on morphology and geography. The resulting morphological groups are then tested as hypothesized lineages using phylogenetic analyses. Based on the totality of evidence, a new taxonomic treatment of the genus is proposed recognizing 30 taxa in 22 species. This treatment includes life history, discussion and illustrations of morphological characters useful in identification, and conservation information relevant to the genus. A key to all taxa is presented, followed by morphological descriptions, synonymy, common names, typifications, distribution maps, phenology, conservation status, notes, and photographs. Morse, 2022, Systematics and Conservation of the Genus Malacothamnus (Malvaceae)

2022 New plants and significant observations

Boykinia occidentalis, COAST BOYKINIA. For many years the last -- and only--- reported Jasper Ridge occurrence was from 1969 by Herb Dengler, who saw it on the ". . . north bank of San Fransquito Creek . . . just above the 'falls' in the creek." In September, 2021, members of the Jasper Ridge herbarium took advantage of unusually dry summer conditions to walk significant stretches of San Francisquito creek. On 9/26/2021 they rediscovered Boykinia in the same location near the falls, reporting 50+ plants in various stages of maturity. The following year, on 7/5/2022, herbarium members revisited this location and confirmed the population with new Calflora observations. (Diane Renshaw)

April 29:

* Navarretia mellita, Honeyscented pincushionplant, has never been included on Jasper Ridge plant lists. After finding patches on the SW-facing slope in sandy soil openings between Artemisia californica in the Rattlesnake Rocks area, a 1914 LeRoy Abrams "Searsville Lake" voucher was located at RSA. The Navarettia grows with:

* Polycarpon depressum, California polycarpon, first vouchered for JRBP a week ago upslope from Trail 9 in the intermediate oak zone.

* Nuttallanthus texanus, Texas Toadflax, not seen by the Herbarium group for 15 years.

* A hitherto unknown second location for Leptosiphon pygmaeus ssp. continentalis. Trail 11 observations.

* Triodanis biflora, Venus' looking glass, not reported for Jasper Ridge since 1979.

* Tiny form (3 cm tall) of Festuca octoflora, which has now been located in a few additional scurry zones and bare areas.

April 24:

* Agrostis microphylla (Locally Rare in the Santa Cruz Mountains). A poor year for this small annual grass.

* Allium amplectens leafing out. Three locations in the Santa Cruz Mtns.

* Allium lacunosum lacunosum leafing out. JRBP and Edgewood Preserve only confirmed locs in Santa Cruz Mtns Bioregion.

* Dichelostemma multiflorum, Round-Tooth Ookow (Locally rare in the Santa Cruz Mtns). Earlier observations.

April 19: Zeltnera davyi, Davy's centaury

April 12:

* Githopsis specularioides, Common Bluecup. First voucher specimen.

* Hesperevax acaulis var. ambusticola, Fire evax.

* Pentachaeta alsinoides, Tiny pygmydaisy. First report since 1961.

April 4: Amsinckia lunaris, Bent flowered fiddleneck. First voucher specimen.

March 13-14:

* Ravenella griffinii (syn. Campanula griffinii). JRBP is the only confirmed location in the Santa Cruz Mtns Bioregion. Genus honoring Peter Raven; species epithet for James Griffin, UC Hastings Preserve.

* Stellaria nitens, Shining chickweed. Tiny annual.

* Collinsia sparsiflora var. collina, Trail A serpentinite and Trails 5-6. Many plants both color forms. Locally Rare or Locally Uncommon.

* Allium falcifolium, Brewer's onion. JRBP and Umunhum only confirmed locs in the Santa Cruz Mtns.

* Erythranthe microphylla, Small leaved monkeyflower, (syn. Mimulus guttatus var. microphyllus. Locally Rare or Locally Uncommon.

* Diplacus douglasii and Scribneria bolanderi. Adjacent in same scurry zone. Locally Rare.

5/27/2021: Local Rainfall Averages

If my stats are accurate, this is the situation for rainfall in Portola Valley. I realize the season doesn't officially end until June 30th but the chance of getting measurable rainfall keeps getting slimmer and slimmer -- Bob Dodge

(1) 2016 - 2017 35.75″; 2017 - 2018 14.75″; 2018 - 2019 25.55″

(2) rain years 2019-2020, 2020-2021; total rain: 2019-2020 11.45

(3) Last measurable rainfall March 19; no measurable rainfall in the past 69 days

Complete index from 1893 to present

Blue line 5 year average, red line inches/rain year; combining of data from four sites: Nathorst Lane(PV), Ladera, Mapache(PV) and Searsville Lake that covers almost the entire lifespan of the Searsville Dam. My thanks to Trevor for the Searsville Lake records and to Tor and Nancy Lund for the Mapache and Nathorst sites records from the Town of Portola Valley historical records. The data from Ladera is from my own weather records covering the past 20 years. -- Bob Dodge

Fall rainfall or lack of rainfall most would say. WHERE IS THE RAIN? Ten year graph -- Bob Dodge

1/8/2020: Hennediella stanfordensis (moss) found on the Preserve

October 7, 2020, the members of the Oakmead Herbarium were invited to spend a few hours on the drying bed of Searsville Lake to survey plants appearing there. Besides the usual low level from an extended dry season, the lake had been drawn down especially far this year in order to make observations. This allowed us to walk onto parts of the lakebed that would usually be covered with water or too soft for foot traffic. As the clay soils in the center of the lake dried, cracks opened. Far from the remaining lake water the cracks were drier, but they became deeper and damper in the central area usually underwater. On the north and east facing walls of these wetter cracks patches of moss were found growing from about 2-25 cm down. The moss was sent to Jim Shevock of the California Academy of Sciences and identified by David Toren. This moss was first discovered in a garden near the intersection of Mayfield and Frenchmans Road on the Stanford Campus in 1951 by biology professor W. C. Steere (and originally given the name Tortula stanfordensis). This moss grows in only a few widely separated areas of the world, the San Francisco Peninsula being one of them. The discovery is the first time the moss has been recorded on campus since the original collection was made. — Rebecca Reynolds

12/28/2020

Looking back: Invasion of Serpentine prairie by nonnative grasses

"One of the most noticeable features of the data set is the invasion of the serpentine grassland by the nonnative grass Bromus hordeaceus. The serpentine grassland has remained relatively free of the nonnative grasses, mostly of Mediterranean origin, that dominate most California grasslands, mainly because of the low nutrient status and chemical composition of the serpentine soils (Kruckeberg 1954, McNaughton 1968, Huenneke et al. 1990, Streit et al. 1993). Previous studies have indicated that invasion is promoted either when nutrient availability is increased experimentally (Hobbs et al. 1988, Huenneke et al. 1990) or in response to NOx pollution (Weiss 1999) and also in response to episodically high rainfall events (Hobbs and Mooney 1991, 1995). This fits with the idea that short-term enhancements of resource availability can enhance community invasibility (Davis et al. 2000, Gross et al. 2005). The long-term data presented here clearly track the invasion of the grassland by B. hordeaceus following the 1982–1983 El Niño event and again following the 1997–1998 event. It is interesting to note that abundance reached a peak several years after the El Niño event in both cases and that it started to increase in frequency prior to the 1997–1998 event, possibly in response to the higher rainfall in 1994–1995 season.

It is also interesting to examine not just the trigger for the invasion but also the possible reasons for the sudden decline of B. hordeaceus following the invasion that commenced in 1984. The grass reached peak abundance in 1986 but then abundance fell dramatically in 1987. This coincided with the 1986–1987 rainfall season that was marked by a period of heavy rain in September followed by a pronounced period without further rain and the lowest total rainfall amount recorded during this study. Observations suggested that B. hordeaceus germinated in abundance following the September rains, but subsequently failed to survive during the ensuing period without significant further rain. It is interesting to speculate that, without this check on B. hordeaceus populations, the species may have persisted at high levels of abundance for considerably longer despite overall lower rainfall amounts. Ongoing analysis of the experiment will reveal whether this happens following the second invasion starting in the late 1990s.

Invasion by B. hordeaceus and other nonnative grasses significantly alters the serpentine grassland by forming dense patches within which few native species survive and leaving a persistent thatch that prevents further recolonization by native species and alters the local nutrient dynamics (Hobbs et al. 1988, Huenneke et al. 1990, Weiss 1999). Competition from nonnative species has also been shown to impact negatively native perennial bunchgrass species such as Nasella pulchra in other California grasslands (Dyer and Rice 1999, Brown and Rice 2000, Corbin and D’Antonio 2004). The invasion process may also be enhanced by increasing levels of nitrogen input. While this process can be interrupted by gopher disturbance, there is a risk that long-term dominance by B. hordeaceus could significantly reduce the grassland diversity locally. From a management perspective, in a situation such as Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve, it will be important to monitor the situation carefully and perhaps consider initiating interventive management such as seasonal grazing or mowing to reduce nonnative grass abundance."

— Hobbs et al (2007) Long-Term Data Reveal Complex Dynamics in Grassland in Relation to Climate and Disturbance. Related fieldnote by Herb Dengler (1974) and our postcard Spring bloom on the serpentine prairie

2020-10: Disease Burden of Jasper Ridge Grasses

Two new publications from the lab of Professor Erin Mordecai report that the disease burden faced by Jasper Ridge grasses due to pathogenic fungi depends on many of the same factors that affect disease susceptibility in humans—the background environment, proximity to infected individuals, overall pathogen burden, and even the weather. You can read more about the publications here.

2020-10: Searsville Lakebed Survey

The exceptional drawdown of Searsville Reservoir has provided a rare opportunity to survey for plant species that are unique to the dry lakebed. The survey encountered a native species previously unreported at Jasper Ridge, Sesuvium verrucosum, or Western sea-purslane. It is an uncommon species of seasonally dry flats or the margins of saline wetlands. It may have grown from seed carried to Searsville by shorebirds. It is one of the few California natives in the ice-plant family, Aizoaceae, and the first member of that family recorded at Jasper Ridge. 10/7/2020 Searsville Lakebed Survey plant list

2020-1: Winter walking along San Francisquito Creek

► Mapping riparian corridors: Invasives (Acacia) and sensitive plants: Special Status: Rare.kmz and Dirca | Locally Rare (.kmz) | Watch List (.kmz) | Willow sampling in marsh and creeks

There are two gems, visited again and again by plant aficionados, along San Francisquito Creek, the Douglas Iris site and the Leopard lily site, the former is on an alluvial terrace and the latter on serpentinite*. Not the time for a creek walk for most vascular plants in flower, though bryophytes are flourishing including the California endemic Bestia longipes on sandstone outcrops. This is exactly the time to appreciate some of the most serious threats.

Changes to the native vegetation in the upper reaches of San Francisquito Creek have been noted over decades during a hundred or more walks through the creek corridor by Herbarium members, and continuing decline is inevitable, based on our qualitative assessments. In our 2008 Status of Vascular Plants: A report produced as part of the State of the Preserve assessment Jasper Ridge creeks were already, not surprisingly, characterized as "severely impacted by herbaceous and woody" weedy introductions**.

Now is the time to visit San Francisquito Creek on trails1 and 2 in order to clearly observe two major threats to the native flora: French broom (Genista monspessulana) and Silver wattle (Acacia dealbata). Evergreen, these Old World woody plants are now in your face, dominating extensive sections of the north streambank. Most of the native creek vegetation is deciduous and currently without leaves. These include woody trees and shrubs such as Elderberry (Sambucus racemosa), Black walnut (Juglans hindsii), Willow (Salix lasiolepis), Bigleaf maple (Acer macrophyllum), Western burning bush (Euonymus occidentalis), Black cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa), American dogwood (Cornus sericea), Snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus laevigatus), White alder (Alnus rhombifolia), Califonia hazel (Corylus cornuta californica), Pacific ninebark (Physocarpus capitatus), Oceanspray (Holodiscus discolor), Western Virgin's bower (Clematis ligusticifolia); and herbaceous perennials such as Torrent sedge (Carex nudata), Wild licorice (Glycyrrhiza lepidota) and Durango root (Datisca glomerata). So enjoy the diversity while one still can, even without their foliage.

Note

* Prepare for spring and early summer visits by reading Toni Corelli's Some Plants growing on Trail 1 Serpentine and by browsing the Herbarium photo archive.

** The communities with more complete woody canopies, excepting riparian areas, continue to be less susceptible to invasion by introduced plant species. However, the recent invaders Ehrharta erecta (panic veldt grass), Brachypodium sylvaticum (slender false brome), and Geranium purpureum/robertianum could dramatically alter the herbaceous layer of the preserve's mesic woodlands and riparian corridors. The riparian zones have already been severely impacted by herbaceous and woody aliens Genista monspessulana (French broom), Acacia dealbata (silver wattle) and a lesser extent Ailanthus altissima (tree of heaven). Notably, the riparian areas continue to provide habitat for numerous native plants from Polystichum dudleyi (Dudley's shield fern) to Lilium pardalinum ssp. pardalinum (leopard lily), and their canopies are still dominated by native trees and the shrub understory by natives where not replaced by French broom infestations. Furthermore, the creek corridor below the dam has not yet been invaded by Senecio mikanioides (Cape-ivy, German-ivy), Arundo donax (giant reed), or Rubus discolor (Himalayan blackberry) [as of 2008] as have many local drainages downstream from urban development. . . Vinca major (greater periwinkle) is persistent in riparian areas but seldom forms extensive mats, and Eucalyptus globulus (blue gum) is not established in San Francisquito or Bear Creeks and does not behave as a weed anywhere on the preserve. Conspicuous plants in the major creek beds include the native Carex nudata (torrent sedge) and the exotic invasive Agrostis viridis (water bentgrass), along with a suite of other aliens. There is at least one large, seed-producing Cortaderia selloana (pampas grass) about a hundred yards west of San Francisquito Creek at the end of Trail 2 that should be removed, and another in the unfenced area west of Portola Road. (slightly updated from 2008 Status of Vascular Plants: A report produced as part of the State of the Preserve assessment, p.18)

2019: Herbarium fieldwork

The group's fieldwork activity focuses on monitoring the Preserve's floristically-rich sites (many listed on our place-names page) as well as specific plants, typically those plants that are special status and/or locally rare on the Preserve, in the county or throughout the Santa Cruz Mountains bioregion. Some of these plants have not have been observed for many years; dissapearances and declines are listed on the Oakmead website). We also carry-out random transects and regular surveys--frequently retracing former Herb Dengler routes gleaned from his notebooks--covering most sectors of the Preserve. Some are repeated more than once annually such as creeks, marsh and lakeshore. Our activity is documented by georeferenced records in our photo archive, voucher specimens in the Oakmead Herbarium and online records in the Consortium of California Herbaria, and Calflora observations. One can join us for many of the outing from 2010 to the present via Alice Cumming's JRBP photo albums.

Notable observations and discoveries are also mentioned in our floral postcard to affiliates dated 5/15/2019, such as:

A number of infrequently seen plants are in bloom this season. Near the top of the list of local rarity is the 5 cm tall Griffin's bellflower, Campanula griffinii, last documented in 2013, known only from Jasper Ridge in the Santa Cruz Mountains bioregion. Another is California cottonrose, which had never before been vouchered for the Preserve. In the California cottonrose photo are some seemingly dried-up grasses, the exceedingly locally rare native annual Sixweeks grass, Festuca octoflora. Jasper Ridge has a dependable population of the tiny annual native Scribner grass, Scribneria bolanderi, with 4 bioregion locations. Showier is Abrams' woolly star, also known from 4 locations in the bioriegion. Pigmy linanthus, Leptosiphon pygmaeus, is only known from Jasper Ridge and the large and floristically rich Sierra Azul Preserve in the bioregion. These tiny plants, and many others, frequently find favorable habitat in scurry zones of different ecotones, and also at the sides of trails and roads where there is often limited competition but also limited disturbance.

Oher notable observations

- Many-flowered brodiaea (Dichelostemma multiflorum). Currently known in the Santa Cruz Mountains bioregion from a very few plants at a single Jasper Ridge location; first reported by S. Burnham in 1907. Jasper Ridge is at the plant's southern limit of distribution

- California shield fern (Polystichum californicum). Purported sterile hybrid whose ancestors in our region are the locally common Sword fern (P. munitum) and the less common Dudley's shield fern (P. dudleyi). All three species were found growing within a few feet of one another.

- Yellow monkey flower (Mimulus guttata), common monkey flower, has been segregated into into several new species of which the Preserve has two, the perennial Erythranthe guttata and annual Erythranthe microphylla.

- Narrow boisduvalia (Epilobium torreyi). Not known to be present since 1981. Only two verified occurrences in the Santa Cruz Mountains in San Mateo and Santa Clara counties.

- Spreading wood fern (Dryopteris expansa). Previously known only on the Preserve from a 1930 voucher specimen at Rancho Santa Ana Botanical Garden, Claremont.

2019: Claytonia

May 18 was the annual ant survey and a reminder that ants, other insects and flowering plants represent a classic case of coevolution over the past 90 million years (give or take). Elaiosomes are seed appendages, stocked full of lipids and proteins; they attract ants and are believed to promote seed dispersal. Ants carry the seed to their nest and eat the elaiosomes. This does not harm the seed, and may in some cases help with germination. When systems co-evolve, we need to ask: how did the interaction evolve, which came first, and what are the benefits to the participants? Did plants develop elaiosomes to attract ants, or do elaisomes help with water intake and germination, and ants have learned to take advantage of the situation? The answer may be be a bit of both.

Claytonia (Miners' lettuce) is a common and widespread genus in the family Montiaceae at Jasper Ridge whose seeds have elaiosome appendages. When ripe, the seeds are expelled explosively, scattering them. What role do ants play in supplementing dispersal for this common, well-known plant?

- Claytonia exigua ssp. exigua SLENDER CLAYTONIA

- Claytonia parviflora ssp. parviflora SMALL-FLOWERED CLAYTONIA

- Claytonia perfoliata ssp. perfoliata MINER'S LETTUCE

2019: How many plants grow here?

The Oakmead Herbarium online listing of native and naturalized plants currently includes 820 vascular plants and 77 bryophytes. These totals represent terminal aka minimum level taxa (species, subspecies, varieties) in the Jepson eFlora. The vascular plant total is somewhat over 10% of the taxa treated for California by the Jepson eFlora when adjusted for differing treatment of some hybrids and non-natives.1 Native taxa are currently 70% of the vascular flora. The Herbarium has 6,000+ voucher sheets of all bryophytes and 900+ vascular plants, including garden and agricultural ephemerals -- waifs -- and other adventitious plants not included in the Preserve's "official" flora. We track almost 1000 plants in our database including a significant number of under-documented reports. The native and naturalized flora referenced above includes taxa -- estimated at 3-4% of total -- known only from historical vouchers or presumed to have disappeared in recent from the Preserve; see the list of species loss and declines All such plants are annotated in the online plant list. Finally keep in mind that there are other and perhaps more significant measures of the richness of the Preserve's flora . . . read more

1 Scientific names follow the Jepson eFlora; we also include plants and names not treated therein. Following the Marin Flora, 2nd ed, 2007: “We include here as naturalized species those that are established and have a true competitive status without cultivation whether the plant is aggressively spreading or seems only passively and locally established. . . . Experience has shown that the waifs of today may become the weeds of tomorrow". We also include named hybrids not given taxonomic status in TJM2, e.g., Elymus x hansenii, Quercus x jolonensis.

2019: Plant Blindness

Most state laws provide fewer and weaker protections for endangered plants than the Federal Endangered Species Act. Like the Federal act, most State laws provide no or minimal protection for endangered plants on private lands. Penalties for violation of state laws are usually minimal. Very few state laws require state agencies to consult on their projects that may damage endangered plants. Very few have provisions for the designation of critical habitat or a requirement to develop recovery plans. Nevertheless, all state laws designate an agency responsible for endangered plants and give the agency the job of developing a state list. The agency is usually responsible for public information, education, and conservation activities in partnership with other agencies, organizations, and individuals. https://www.fs.

California is somewhat exceptional, in that CEQA requires review of not only all federal and state-listed rare and endangered plants, but also requires consideration of plants with unofficial listing status (e.g., most notably CNPS listed taxa). Most of the CNPS-ranked plants are not on state or federal lists. Additionally, CEQA requires consideration of plants of Local Rarity.

2013-5: The Preserve at 40 (Stanford Report)

See also 12/28/2020: Looking back: Invasion of Serpentine prairie by nonnative grasses

One of those questions, and a current focus of research of the preserve, is how to best go about successfully preserving nature, or what is known as intervention ecology. "When Jasper Ridge was formally designated as a preserve, there was good reason to believe that it was a self-sustaining environment, that natural processes would sustain the natural biodiversity, for example," said Chiariello. "That worked for a while, but it's now clear that with invasive species and other pressures that won't be a sustainable practice for the future." In 2004, a new strategic plan for Jasper Ridge revised the founding "do-not-interfere" policy and opened a case-by-case discussion on how to strategically tweak an existing ecosystem – either at the preserve or elsewhere – to put it back on a natural path. "We're really interested in restoration now, but to do this effectively we need to first know, for instance, how important it is that you seed an ecosystem with a critical species first so that it can take off on its own," Chiariello said. "We can begin to understand that with the Mimulus system." As research in the preserve has moved in these directions, the types of faculty and students who gravitate to the preserve have shifted as well. https://news.stanford.edu/news/2013/may/jasper-ridge-anniversary-051013....

Transformation of serpentine prairie

JRBP’s some 60 acres of serpentine soils is a small portion of the 3000+ acres exposed in the Bay Area (McCarten, 1993). It is a beautiful landscape of native prairie grading variously into serpentine chaparral, woodland, and oak savanna. There are no known, federal or state listed rare plants or animals associated with the Jasper Ridge serpentine, though there are some special status and locally rare plants such as Agrostis microphylla, Allium peninsulare francsicanum, Ancistrocarphus filagineus, Hesperevax acaulis ambusticola, Lessingia hololeuca, Ravenella (Campanula) griffinii. The remaining bay checkerspot butterfly population appears to have been extinct at JRBP as of 1999 (Weiss, 1999).

The ridgetop has also not been grazed since 1960. Grazing removal has been detrimental to the native plant diversity of other sites (Weiss, 1999; Edwards, 1992, 1995; Hopkinson, 2008). Prevailing NW winds have resulted in less Nitrogen deposition from air pollution at JRBP than at some other Bay Area sites (Weiss, 1999). Increased N favors annual grasses by mitigating some of the harsh chemistry for plants of serpentine soils. JRBP serpentine soils had earlier been invaded by Bromus hordeaceus (Hobbs & Mooney, 1995). An increase of Italian ryegrass in 1998 corresponded with record El Niño rainfall (Weiss, 1999). Lolium multiflorum appears in all JRBP floras. The earliest record for Lolium growing in the serpentine is from Herb Dengler’s 1962/63 fieldnotes. On May 19, 1962 he writes, evidently with reference to both Bromus hordeaceus and Lolium, “Mediterranian grass has successfully invaded the serp this year.” Springer (1938) found Italian rye grass to be “frequent along roadsides and in open fields and on openly wooded slopes near roads.” Thomas (1961) did not report Italian rye grass growing on serpentine in the Santa Cruz Mountains. McNaughton (1968) did not report Italian rye grass on serpentine. In 1990 the third revised edition of the Jasper Ridge Docent Handbook still identified only soft chess from among the Preserve’s naturalized grasses growing on serpentine. Armstrong and Huenneke (1993) documented Lolium was common in serpentine by 1985-86 and that it was negatively effected by drought. In 2001 and 2002 Lolium accounted for 32% and 20%, respectively, cover of Stuart Weiss’ JRBP serpentine transects (Weiss, 2002). In Spring 2006 the herbarium crew assisted in two relevant-to-this-issue surveys, a repeat of the Armstrong and Huenneke transect; and the vegetation component of a small mammal inventory. It is our impression that Lolium may approach a frequency of 80% to 90% in these serpentine quadrats. Hobbs et al. (2007, p.554-45) data shows lower coverage and frequency of Lolium for 1983-2003. The herbarium crew has not examined Hobbs' 50 x 50 m quadrats. Also see CNPS Vegetation Rapid Assessment Field Form JASP0001 3/25/2008.

Weiss writes:

The invasive grasses that have dramatically changed California’s grasslands are poised to dominate the last refugia for the native grassland flora and fauna, given the chance. That chance is provided by smog-induced fertilization, but only with the additional land-use change of removing grazing . . . It is ironic that grazing, which has contributed so greatly to the transformation of California’s native grasslands, may prove necessary for their maintenance . . .

—Weiss, 1999, p. 1485

Exhaust from cars, about 110,000 vehicles a day on Highway 101, along with other urban sources, annually deposit 15 to 20 pounds of nitrogen per acre on Coyote Ridge south and east of JRBP, according to Weiss's monitoring equipment.

Some of the nitrogen is absorbed by living plants, while small particles of the pollutant stick to plants and the ground and are washed into the soil by rain. By contrast, pollution from power plants and vehicles each year deposits just four to five pounds of nitrogen per acre on Jasper Ridge, a Stanford University biological reserve half an hour away. Washington Post

However, even as smog-derived Nitrogen deposition is not as great at JRBP (upwind from most pollution sources) as it is for other serpentine grasslands that are downwind, the spread of Lolium shows other factors can and will contribute to annual grass invasions, and that once introduced, some naturalized plants will have the genetic adaptability to persist on serpentine and other nutrient-poor soils.

- Hobbs, R. et. al. 2007. Long-term data reveal complex dynamics in grassland in relation to climate and disturbance. Ecological Monographs: Vol. 77, No. 4, pp. 545-568.

- Hobbs, R; Mooney, H. 1985. Community and population dynamics of serpentine grassland annuals in relation to gopher disturbance. Oecologia 67:342-351.

- Hobbs, R; Mooney, H. 1986. Community changes following shrub invasion of grassland. Oecologia 70:508-513.

- Hopkinson, P. et al. 2008. Italian ryegrass: A New Central California Dominant? Fremontia 36: 20-24.

- Weiss, S. 1999. Cars, cows, and checkerspot butterflies: nitrogen deposition and management of nutrient-poor grasslands for a threatened species. Conservation Biology 13:1476-1486.

- Weiss, S. 2003. Serpentine grassland restoration at Edgewood Park. CNGA Grasslands 13:7.

- Weiss, S. 2006. Impacts of nitrogen deposition on California ecosystems and biodiversity. CEC-500-2005-165, California Energy Commission.

- Weiss, S. 2010. Atmospheric Nitrogen Deposition and Conservation: ". . . the biggest global change nobody ever heard of. . ." http://www.creeksidescience.com/nitrogen.html (4/13/2010).

2008: Quercus aff. berberridifolia (Q. dumosa misapplied)

There is a shrub occasional on the Ridge, 3-6 ft. tall, sometimes in groups of a few individuals, sometime single, usually on northern slopes 500-600 feet elevation. We have never observed acorns. The leaves are adaxially ± flat to wavy, ± shiny, green; abaxially pale green, margin mucro- or spine-toothed. We have occasionally noticed the adaxial leaf feature emphasized in Jepson II: "with minute appressed stellate hairs." Collections have been made, and some plants in the field are marked with green tape. Paul Heiple proposes these are hybrids.

Treatment in Jepson 2 by the late John Tucker

Q. berberidifolia Liebm. Shrub 1-3 m or ± tree > 3 m, evergreen. LF: 1.5-3 cm; petiole 2-4 mm; blade oblong, elliptic, or ± round, adaxially ± flat to wavy, ± shiny, green, abaxially with minute appressed stellate hairs, dull, pale green, tip gen rounded, margin mucro- or spine-toothed. FR: cup 12-20 mm wide, 5-10 mm deep, hemispheric to bowl-shaped, thick, scales tubercled; nut 10-30 mm, gen ovoid, tip obtuse to acute, shell glabrous inside; mature yr 1. Dry slopes, chaparral; 100-1800 m. KR, NCoR, CaRH, SNF, Teh, ScV (Sutter Buttes), CW, SW; Baja CA. Hybrids with Quercus durata, Quercus engelmannii, Quercus garryana (Quercus howellii J.M. Tucker), Quercus john-tuckeri, Quercus lobata.

Local references to Q. dumosa

- Q. dumosa was reported by Cooper (1922, p.26) as a constituent of the climax chaparral association on Jasper Ridge. His research area was just south of the current southern boundary of the Preserve. Other oaks in this association were gold cup (Chrysolepis chrysophylla), leather (Q. durata), interior live (Q. wizlizenii). He notes that all are evergreen, Q. dumosa barely so.

- The Preserve's first plant list (Springer, 1935) doesn't list Q. dumosa. It does include Quercus sp., found in the chaparral.

- Duncan Porter (1962) lists Q. dumosa and indicates that is was vouchered in the Dudley Herbarium (voucher # 100665). This voucher was later redetermined as Q. durata.

- Dengler (1975) does not list Q. dumosa though he lists a number of hybrids [Q kellog x Q. wizlizenii (morehus); Q. agrifolia x Q. wizlizenii; Q. agrifolia x Q. kellog; Q. doug x Q. lobata; Q doug x Q. durata].

- There are transcribed lecture notes of Mooney (1978-1979) Jasper Ridge Plant Communities [Lecture Notes], makes reference to seven oaks at JR and a specific example in the field of Q. dumosa.

References

Cooper, William. 1922. The broad-sclerophyll vegetation of California: an ecological study of chaparral and its related communities . Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington.

Dengler, H. 1975. A List of Vascular Plants of Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve

Mooney, H. 1978-79. Jasper Ridge Plant Communities

Porter, D. 1962. The vascular plants of the Jasper Ridge Biological Experimental Area of Stanford. Dept. Biol. Sciences. Research Report no. 2.

Springer, M. 1935. A floristic and ecologic study of Jasper Ridge. Thesis. Leland Stanford Junior University.

2007: Nona on Herb Dengler and William Cooper

Herb Dengler wrote in a postscript to a letter dated April 18, 1962:

Fifty years ago, Dr. W. S. Cooper, then of Carnegie Institute, began his studies of broad-sclerophyll (Oakwood land-Chaparral) vegetation of California on Jasper Ridge. His work stands today as a classic. The detailed instrumental studies -- the basis for his findings, were in 15 meter square quadrats (I'm not referring to the fenced quadrats seen on the Ridge today). Anyway, I was fortunate in relocating these, and with photos supplied by Dr. Cooper, I have been able to make some interesting comparisons. Almost plant for plant Chamise (Adenostoma fasciculatum), and Manzanita (Arctostaphylos crustacea) remain as they were then. Some Adenostoma that were 18 inches tall then are still 18 inches tall, and little "scrub" oaks (Quercus durata) which were present then are only 3 feet tall. There is a whole sequence of surprising circumstances surrounding this comparison. I've just about finished this problem. Last month Dr. Cooper sent me all of his notes relating to a brush fire in the chaparral in 1912. Twenty-three stumps of Adenostoma and one burned clump of Toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia) were left standing in one 15 meter square quadrat. These all sprouted shortly, and flourished. The second year, the bare ground was covered with over 3000 herbs, but with succeeding years these did not appear because of the dense growth of Ceanothus, seedlings which gained ascendancy. In 12 years the Ceanothus plants were 8 to 10 feet tall, seeming to surpass all else, but as is their habit, they died off so that by the end of the 15th year substantially all that was left were the original shrubs of Chamise and Toyon -- the same plants that existed before the fire. The course of this was in the complete absence of human disturbance. Hillside brush that composes the chaparral may not appear imposing, but the vitality of these plants is very great when left undisturbed and may vie with oaks and redwoods for length of life. (Nona Chiariello, email, 18 April 2007)

1998: A walk with Herb Dengler

For Dengler, it has been a lifelong gift . . . “It’s been my honor to know this ridge,” he says. “It really is something of a miracle, with all the growth all around us, that this special place is still here.”